Sleep, Work, and COVID-19: In-Depth Study

Medically Reviewed by Dr. Sahil Chopra

You’ve seen the headlines. Publications like The Atlantic and Bloomberg are calling out the Coronavirus for creating the largest work from home experiment. As the outbreak spread, governments and companies across the globe responded. More people than ever are working from home. We know this.

What we don’t know yet is this: how is the “new normal” of working from home affecting our productivity? How many people have gone from working at a desk in their office to a bed in their home? How is that affecting their sleep, and consequently their productivity?

Our mission is to help people better understand how their lives impact their sleep, and how their sleep impacts their lives. We do that by providing evidence-based sleep information and news. That’s why we set out to survey over 1,000 Americans to see how the new work-from-home lifestyle has affected their sleep and productivity.

What we found may surprise you.

How Has Quarantine Changed Our Sleep?

Key Findings

- 70 percent of people now report having 2 or more sleep disruptions/month, an increase of 37 percent from before the Coronavirus outbreak.

- One in five now report having trouble sleeping 3 to 5 times a week, up 220 percent from before the outbreak.

- 47 percent of those who previously “never” had trouble sleeping due to stress or worry are now experiencing sleep disruptions once or more in the last month.

- Women were significantly more likely than men to report sleep disruptions, both before and after the pandemic.

- Women were also more likely to report an increase in disturbed sleep since the spread of the Coronavirus.

The global pandemic has certainly changed how we work. How has it changed our sleep? We asked our respondents.

People More Likely to Sleep Too Much, Too Little, and Not Well, Since COVID-19 Crisis

While about a third felt that their sleep, both in terms of amount and quality, stayed the same, others noted that both the amount of sleep they got and the quality of it has decreased. Overall, people were more likely to report getting less sleep and less restful sleep, than they were to report having better sleep.

Before the pandemic, just under 50 percent of our respondents were enjoying a healthy amount of sleep (defined as 7 to 8 hours) on the average night. After the outbreak, that number dropped to 37.5 percent.

Since the COVID-19 crisis and subsequent stay-at-home orders, significantly more people are either under- or over-sleeping.

- 41.6 percent report sleeping six hours or less, with 10 percent of people sleeping fewer than five. While the number of people sleeping 5 to 6 hours has stayed roughly the same, almost twice as many people are sleeping fewer than 5.

- On the other end of the spectrum, 20.8 percent of people are oversleeping, with 4.5 percent spending over 9 hours asleep each night, an over 100 percent increase from before the Coronavirus spread.

Feelings of Anxiousness, Stress, and Worry Keeping People Up at Night

We also asked respondents how frequently they were kept awake or woke up in the night with feelings of anxiousness, stress, or worry, and charted how those responses changed before and after the Coronavirus spread.

What we found was concerning. Across the board, people are experiencing significantly more sleep disruption due to feelings of anxiousness, stress, or worry. They’re either having a hard time falling asleep, or finding themselves waking up during the night.

- Before the Coronavirus outbreak, roughly half (49 percent) of people reported either having no sleep disruptions at all, or just one per month.

- After the outbreak, that number dropped to just 30 percent.

Worse, we saw huge gains in the number of people for whom delayed sleep, or sleep disruptions, are becoming a frequent part of life. Before the pandemic, only 6.3 percent of people reported having trouble sleeping due to feelings of anxiousness, stress, or worry several times a week, and less than 3 percent reported experiencing these issues every night.

Since the outbreak, both of those numbers have increased to alarming extents. One in five people (20 percent) now report having trouble sleeping 3 to 5 times a week, up 220 percent from before the outbreak. As for people who experience these issues on a nightly basis, the number nearly tripled.

Of those who “never” had trouble sleeping due to stress or worry before the outbreak, 30 percent now report having trouble at least once a month, with 17 percent having trouble at least once a week. Of those who previously had trouble sleeping at least once or twice a week, nearly half (45 percent) are now experiencing more frequent sleep disruptions, three nights a week or more.

Women Experiencing Sleep Disruptions to a Higher Extent Than Men

We also observed gender differences. Overall, before the COVID-19 crisis, women were significantly more likely than men to report having two or more sleep disruptions a month. Men, on the other hand, were almost twice as likely to report “never” having sleep disruptions. These trends sustained after the outbreak spread.

Women were also more likely to report an increase in disturbed sleep after the Coronavirus outbreak, with 33.5 percent of women experiencing disruptions three times a week or more, compared with only 20.7 percent of men.

Analysis

Since the COVID-19 crisis, significantly more people are engaging in unhealthy sleep (either sleeping too much or too little). Our findings suggest that feelings of anxiousness, stress, and worry may be contributing to the reduction in healthy sleep. Anxiety and stress are linked to undersleep (insomnia), while depression is linked to both under- and oversleep (hypersomnia).

When people are experiencing undue stress, their body produces higher levels of cortisol. In healthy individuals, this stress hormone shares an inverse relationship with melatonin (the sleep hormone). Cortisol levels lower in the evening, as melatonin kicks into production, encouraging your brain to sleep. In the morning, cortisol levels rise to energize your body, as melatonin tapers off.

When people are experiencing stress and having trouble sleeping, their cortisol levels stay elevated, resulting in a state scientists call hyperarousal — where their sleep is less restful. This may explain those late-night awakenings people are experiencing due to stress or worry.

Problematically, not getting enough sleep can increase your stress and tendency to “excessively worry,” as researchers from University of California, Berkeley put it.

In other words, people who are finding themselves sleeping less since they’ve been sheltering-in-place may continue to experience disturbed sleep amid increased levels of stress — a perfect recipe for worse sleep and more stress.

Those who are sleeping significantly more since the pandemic hit may not be feeling great, either. It may seem like the more sleep the better, but that’s not quite how it works. There is such a thing as too much sleep, and it’s a common symptom of depression.

Along with oversleeping, individuals with depression may experience insomnia (difficulty falling or staying asleep), as well as lethargy and excessive daytime sleepiness during the day. And just as anxiety and sleep share a dangerous bidirectional relationship, so do depression and insomnia. Insomnia increases your risk of depression tenfold.

Our survey results also align with the established research that suggests that women are more prone to insomnia than men. Women are also more likely to experience mental health conditions like depression and anxiety, which can be secondary causes of disturbed sleep and short sleep.

Helpful Tips

If these numbers hit home for you, try these tips to reduce your stress, improve your emotional wellbeing, and sleep better during uncertain times.

- Try meditation. Beginning a short daily meditation practice may be effective for relieving stress and worry, as well as calming your mind to fall asleep. Focus your mind on a single thought or visual image, and breathe slowly in and out.

- Practice deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation techniques before bed. Similarly, you can calm your body down by focusing on your breath, and slowly relaxing each muscle group. Studies have found PMR can help relieve depression and fatigue.

- Take up journaling. Many people are creating quarantine diaries and drawings to help them sort out their thoughts and feelings during the pandemic. Some studies have found writing out a to-do list before bed can help speed up sleep onset.

- Spend time (safely) outdoors. Sunshine can brighten your mood and your day. Spending time in natural light, especially in the morning or midday, can also help reinforce your natural circadian rhythms and sleep cycle. Just maintain a six-foot distance with strangers, and wear a face covering.

- Exercise regularly. Whether it’s following along to a yoga session on Instagram Live or replacing your weightlifting session at the gym with an in-home resistance bands workout, there are plenty of ways to stay fit during the pandemic. Aerobic exercise like walking, jogging, cycling, gardening, and dancing for up to 30 minutes can curb anxiety and depression. Plus, a consistent exercise routine (not too close to bedtime) can improve sleep quality.

Working From Home, or Working From Bed?

Key Findings

- 72 percent of people now report working from bed, up over 50 percent from before the COVID-19 crisis.

- Nearly one in ten people are working most or all of their workweek from bed (24 to 40+ hours).

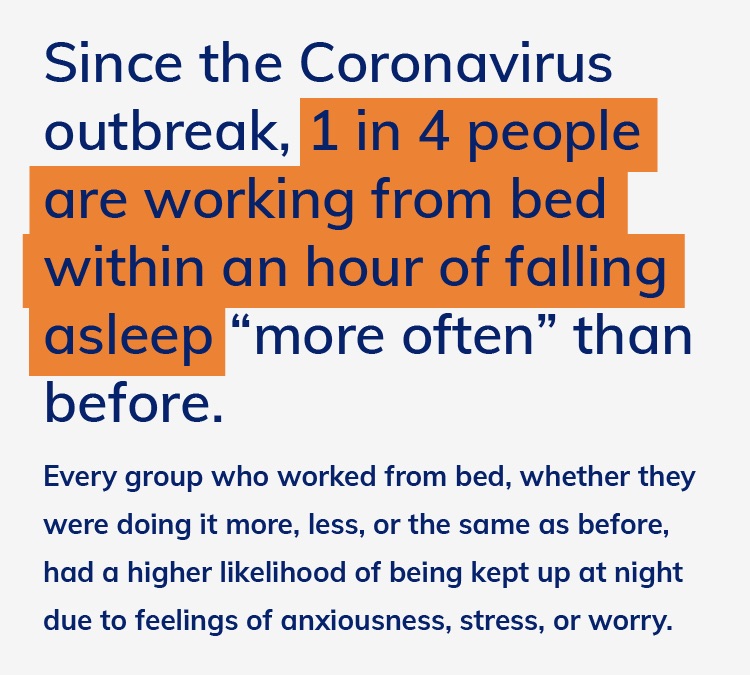

- One in four people report working from bed within an hour of falling asleep “more often” than before.

- Every group who worked from bed, whether they were doing it more, less, or the same as before, had a higher likelihood of being kept up at night due to feelings of anxiousness, stress, or worry.

When we’re stressed and low on sleep, one thing that can fall by the wayside are good habits, especially good sleep habits. Known as “sleep hygiene,” good sleep habits include things like: following a bedtime routine, going to bed and waking up at the same time every day, maintaining a cool and dark sleep environment, and reserving your bed for only bed-related activities like sleep and sex.

That last one is important. Reserving your bed just for sleep activities helps train your brain to associate it as a place of relaxation. When you start to do other things in your bedroom, like work or hobbies, it may impact how easily you can fall asleep.

Working From Bed on the Rise

We asked our respondents how many hours a week they worked from bed, before and after they started sheltering-in-place.

Across the board, more people are spending more time working from bed. Before the Coronavirus spread, over half of people (52.4 percent) of people never worked from their bed when they worked from home. Afterwards, that number nearly decreased by half, down to just 27.7 percent.

Fortunately, most people are limiting the time they spend working from bed. 75.4 percent of people spend 8 hours or less working from bed; that’s the equivalent of one work day per week. However, 8.8 percent of people are working most or all of their workweek from bed (24 to 40+ hours).

Late-Night Working From Bed Also More Common

Another sleep hygiene no-no is doing work or other energizing activity before bed. These kinds of activities activate your mind in ways that can increase stress and energy levels. In other words, they make it difficult to fall asleep.

Before the pandemic, the majority of our respondents got an A+ for this particular sleep habit. 52.2 percent never worked from bed within an hour of falling asleep, and 13.9 percent only did it a few nights a year. While some worked from bed more often than sleep experts would recommend, two-thirds of people didn’t.

Unfortunately, not everyone kept up those good habits once the Coronavirus started to spread. Nearly half of the people who used to never work from bed within an hour of bedtime now report that they do, with only 27.5 percent of people still refraining from doing so. And one in four people (24.6 percent) report that they now work from bed within an hour of falling asleep “more often” than before. Fewer than 13 percent of people are working from bed less often before they fall asleep.

Strong Correlation Between Late-Night Working From Bed and Sleep Disruptions

Moreover, as a group, those who reported never working from bed were also significantly less likely to experience sleep disruptions on a weekly or more frequent basis. Every other group who worked from bed, whether they were doing it more, less, or about the same as before, had a higher likelihood of being kept up at night due to feelings of anxiousness, stress, or worry.

Analysis

The results indicate that people are comfortable working from bed and doing so late at night, despite the detrimental effects that can have on sleep.

Working from bed becomes problematic because it encourages your brain to associate your bed with a place of activity, unrest, and potentially stress (depending on your job), instead of a place of rest and relaxation.

Furthermore, when you’re working from home, you’ve lost a key element of maintaining a work-life balance: an office that exists outside your home. If you begin treating your bedroom as your office, it becomes more difficult to separate work and stress whenever you’re trying to fall asleep.

If working from bed is bad, working from bed right before you fall asleep is even worse. This is thanks to an unassuming villain called blue light. Blue light, like the kind emitted by your computer, phone, and other electronic devices, happens to be the same kind of light we receive from the sun.

When your eyes are flooded with blue light, as they are while you’re working, your brain assumes it’s looking at the sun and that it’s still daytime — so it delays melatonin production, and consequently your sleep. Some studies have charted a nearly direct relationship between screen time and short sleep.

Helpful Tips

If you’ve turned your bed into your office, consider the following sleep hygiene tips to improve your sleep.

- Set up your office outside of your bedroom. The best place for your work is in another room. The couch can be an equally comfortable makeshift desk. If you live in a studio apartment, try working from a chair or the floor instead.

- Remove work materials from the room. Next, remove anything that makes you think of work (or brings up stress) from your bedroom. This tip comes to you from the experts at Harvard Medical School Division of Sleep Medicine.

- Use night-mode or wear blue-light glasses in the evening. If you’re working past the afternoon, limit your exposure to blue light by turning on the “night mode” on your devices. This feature dims your device and uses more red light. Or, try wearing blue-light blocking glasses.

- Stop working at least 1 hour before bed. Instead, fill that last hour with a calming bedtime routine. Use those 60 minutes to relax your mind and body. Power down your electronics (including your smartphone), practice some light stretching or meditation, read a book, or take a bath.

- Follow a regular sleep schedule. With your commute out of the way, your schedule may feel a bit out of sorts. Get back on track with a regular sleep schedule, going to bed and waking up at the same time every day — even weekends.

How Many People Are Working From Home Right Now?

Key Findings

- 81 percent of people are now working their full-time job from home.

- Of those working from home, 36 percent of people are working overtime (40+ hours/week).

- 38 percent are working “full-time” hours (between 24 to 40 hours/week) from home.

- One in four people are clocking in quite a bit less than normal, reporting to work 24 hours or less/week from home.

- A full 5 percent are working fewer than six hours/week from home.

To begin, we wanted to see how many people had transitioned to working their full-time job from home during the Coronavirus outbreak. The vast majority (81 percent) of full-time workers have transitioned from the office to the home office in response to the stay-at-home orders.

People are working from home, but if you’ve spent any time on the internet, you’ve seen the memes that suggest not everyone is actually working from home. Our findings back up those memes. Some people are working overtime to keep their jobs while working from home, while others have found their hours cut short due to stay-at-home orders in their state.

Analysis

Remote work has become increasingly common in the past decade. In 2012, 39 percent reported working from home “at least sometimes” to Gallup. By 2016, four years later, that number had risen 43 percent.

The U.S. Census Bureau has tracked a similar trend. The latest census data in 2018 indicates over 5 percent of Americans work from home full-time.

But even though this number is growing, the trend has skyrocketed as a result of the COVID-19-related quarantining. The majority of our respondents are now working their full-time jobs from home, with 74 percent of them working full-time hours or longer (40+ hours).

Productivity and the Home Office

Key Findings

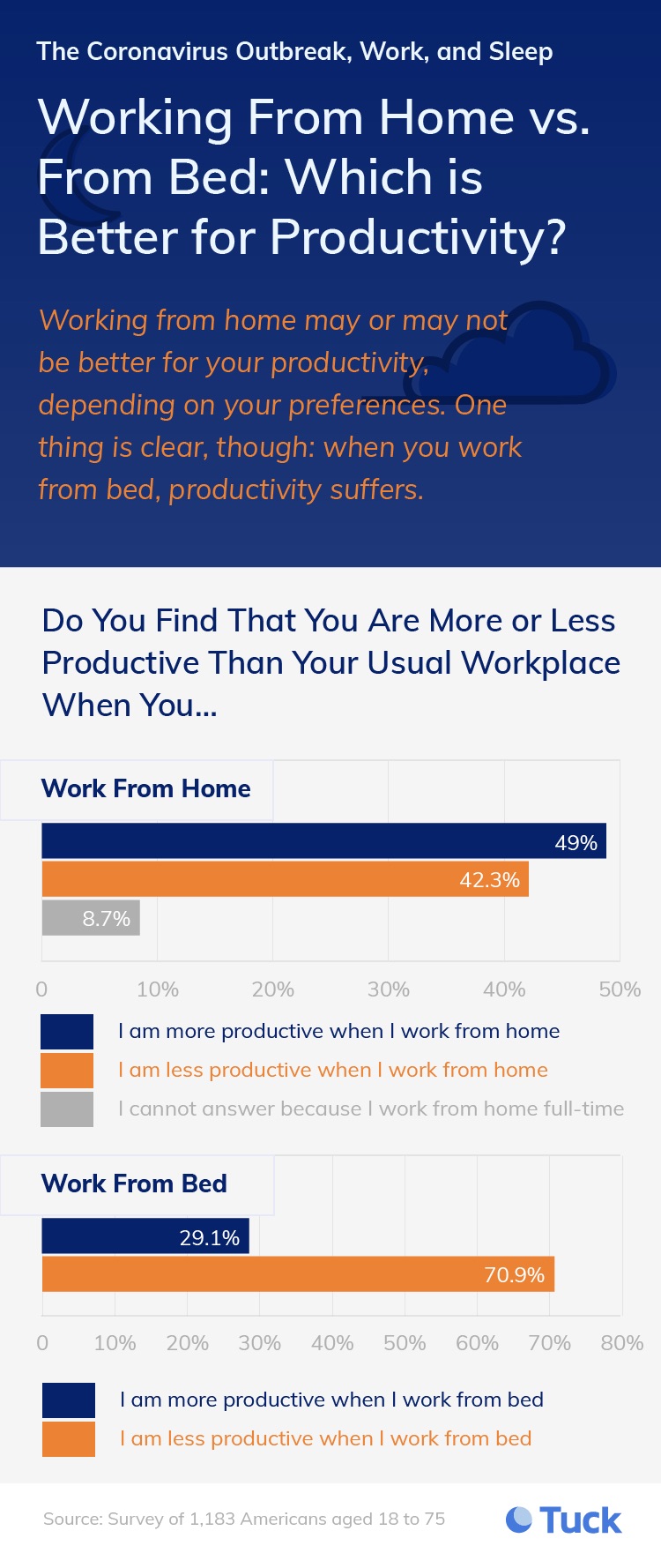

- Slightly more people felt they were more productive when working from home.

- Over 70 percent of people said that their productivity suffers when they work from bed.

- Those who reported working from bed within an hour of falling asleep more often were 50 percent more likely to rate themselves as being less productive and more distracted.

- When working from home, people felt that they were most productive at repetitive and/or administrative tasks, as well as any work that required in-depth focus.

- When working from bed, people felt that they were most productive at only the repetitive and/or administrative tasks.

Working from home, working from bed, or the general stress and worries from the pandemic (or, most likely, all of the above) seem to be affecting people’s sleep. How is it affecting their productivity? Do people feel they are more or less productive when working from home? What about when working from bed?

Productivity Up for Many When Working From Home

To get a baseline, first we wanted to understand how people assessed their general productivity when working from home. We asked respondents, “When you work from home, do you find that you are more or less productive than your usual workplace?”

The results were mixed. Slightly fewer people (42.3 percent) felt they were less productive when they worked from home, while slightly more people felt they were more productive (49.0 percent) working from home.

However, we did find that those who reported working from bed within an hour of falling asleep more often were also 50 percent more likely to rate themselves as being less productive. They were more than 50 percent more likely to rate themselves as being more distracted, as well.

Working From Home Improved Productivity for Two Types of Tasks

Generally, people reported being able to perform two kinds of tasks best when they worked from home:

- Repetitive and/or administrative tasks, such as responding to emails or phone calls

- Work that required in-depth focus, such as creating reports, writing, conducting research, or coding

The general consensus seemed to be that while these types of tasks require different mindsets and attention, they both benefit from being free from the distractions and interruptions common to a typical workplace. As one respondent put it, “I am more productive at focusing because I don’t have coworkers talking to me.”

One respondent referred to these as “heads down tasks” like writing and coding, while many people reported finding it “easier” or “faster” to respond to emails due to “lack of interruptions at home,” or that “home is quieter.” Multiple people referred to concentration in particular being easier at home.

At the same time, others felt it was easier to “catch up” on projects that “don’t require a lot of deep thought or attention,” as well as “repetitive” or “very low priority tasks.”

Productivity Suffers When Working from Bed

While people appear split on whether they find working from home more or less productive, they do tend to agree that a home-based work environment is more conducive to certain tasks. How do the results change when the bed is their home office?

Funnily enough, most people recognize that they are less productive when they work from bed — despite an apparent preference for doing so. Over 70 percent of people acknowledge that their productivity suffers when they work from bed. “I’m not at all productive from bed. Sometimes I’ll sit there and wait for an email,” shared one respondent.

Interestingly, the same people who rate themselves as being less productive when working from bed are nearly 10 times more likely to say they’re also more distracted when working from bed, compared with those who feel they’re more productive from bed.

Additionally, there was a correlation between those who felt more distracted and those who were spending time working from bed more often right before they fell asleep. Those who were spending more time working from bed before bedtime were about 25 percent more likely to report feeling more distracted.

When it comes to working from bed, people expressed a strong preference for having higher productivity with the repetitive/administrative group of tasks. There were very few mentions of the tasks that required in-depth focus, as there had been when we asked about their general productivity when working from home. Instead, people reported using their work-from-bed time to read and respond to emails, schedule meetings, and perform data entry work.

Analysis

Here, we start to see the impact of poor sleep hygiene, and mixing your bedroom with your work environment. Those who work from their beds are significantly more likely to feel less productive, and more distracted.

This contradicts the established evidence that people who work remotely tend to be more productive (as the majority of our respondents agreed, mostly being those who didn’t work from bed).

One famous Stanford study found that working from home boosted productivity by 13 percent, with 9 percent of the gains coming from people taking fewer breaks and working more minutes per shift, and 4 percent coming from individuals making more calls per minute, since they had a quieter work environment. Employee turnover dropped by more than 50 percent.

Based on these promising results, the company rolled out the remote work option across the company. Half of the experiment group switched back to working in the office. Consequently, the productivity among the home workers doubled to 22 percent.

This may suggest that productivity may in some part be tied to our own individual preferences. Currently, due to the pandemic, everyone is being forced to work from home, including those who would rather work in an office—which may be skewing our results. The lead researcher of the Stanford study suggested as much, in a recent interview for Vox. The lack of choice in working remotely may have adverse consequences, and the forced social isolation may result in depression.

Working from home in isolation creates another issue: loneliness. Problematically, short sleep by itself, like the kind experienced by over 40 percent of our respondents since the outbreak, has been linked to social withdrawal and loneliness. This may intensify the feelings people already have and make it harder for them to connect with others, which is important for emotional wellbeing during the pandemic.

As essential as social relationships are to enjoying life, they may also positively impact your physical health. People with stronger social relationships have a 50 percent “increased likelihood of survival.” In other words, having friends and family can be a matter of life or death.

One solution to sleep, productivity, and wellbeing may be deceptively simple: moving the office out of the bedroom. If people separate their sleep and work environment, productivity levels may improve. This distinction of space can help newly remote workers maintain a healthier work-life balance, despite the circumstances.

Helpful Tips

Wherever your home office is, follow these tips for improving your productivity and reducing distractions when working from home.

- Stop working from your bed. Create a separate place for work in your home, whether that’s a kitchen table, a lap desk you use on the couch, or a desk. Aim to keep all work-related materials in this space, so they don’t end up spilling over into the leisure areas of your home.

- Turn off notifications. Notifications from your phone, web browser, or computer can interrupt your thought process and encourage you to turn your attention elsewhere—especially if they are coming from social media or your email inbox. Turn these off whenever you’re focusing on a task.

- Take breaks. Whether it’s a short glance away from your computer every 20 minutes, or a short ten-minute break every couple of hours, make sure to give yourself some screen-free time during the day. Use these breaks to walk your dog, eat lunch or a snack, and check up on those social media notifications you ignored.

- Develop an at-home work schedule. When you went to the office, you followed a schedule day-to-day. Recreate that schedule in your home, and aim to follow it everyday. Start work by a certain hour each morning, and do your best to stop at a certain hour to create a work-life balance.

- Remove temptations. Similar to turning off notifications, ideally you can set up your home office away from things that tend to distract you from working. These may include your TV, bed, gaming console, or craft supplies.

- Use video conferencing. Seeing people’s faces can help strengthen your relationships while you’re apart from loved ones, friends, and colleagues.

Despite its Popularity, Working From Bed Isn’t So Comfortable

Key Findings

- When working from bed, the majority (68 percent) of respondents reported feeling some stiffness or pain, most commonly in their lower back, neck, and/or shoulders.

- The individuals who reported pain when working from bed were also more than twice as likely to report feeling less productive, as well.

- 72.3 percent of respondents agreed that their mattress was suitably comfortable when working from bed.

Beyond the negative implications working from bed has for productivity, how else might it be affecting our health? If people are using their bed as their desk, how does that affect their comfort and sleep? We asked respondents to find out.

Those Who Work From Bed More Likely to Report Stiffness or Pain

When working from bed, the majority (68 percent) of respondents reported feeling some stiffness or pain, most commonly in their lower back, neck, and/or shoulders. Other sources of pain included the upper back, wrists, hands, hips, and knees.

The individuals who reported pain when working from bed were also more than twice as likely to report feeling less productive, as well.

Just one-third of respondents didn’t report experiencing any stiffness or pain when working from bed.

It’s interesting to see that so many people preferred working from bed, despite feeling some stiffness or pain while doing so. It could be that we tend to view our bed as a cozy place, so working from them might provide a sense of comfort during these tense times. That may also explain why, despite feeling stiffness or pain when working from bed, a majority (72.3 percent) of respondents agreed that their mattress was suitably comfortable when working from bed.

Analysis

Our data shows that a majority of people who work from bed experience some sort of stiffness and/or pain while doing so.

Like stress, mental health, and other issues we’ve raised throughout this study, pain can be another obstacle to good sleep. Worse, studies show that a lack of sleep is a reliable predictor of chronic pain.

Pain can also be caused by an unsupportive mattress. Depending on the type of mattress and the quality of their construction, mattresses can lose their supportiveness after a number of years. For example, the average innerspring mattress, the most complained about mattress type in our study, may start to sag within six to six and a half years.

Most people keep their mattress for nearly ten years, so it’s possible that an unsupportive mattress may be contributing to the pain of some of the respondents in our study.

Helpful Tips

If you’re having trouble transitioning from working in bed to somewhere else in your home, or if you’re looking for ways to make your mattress more comfortable, consider the following tips.

- Stop working from bed. We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again. The single best thing you can do to improve your work-life balance, along with potentially improving your productivity, sleep quality, and overall comfort, is to move your office from your bed to a separate place in your home.

- Make your new desk enticing. Set up your dedicated office space with things that make you happy and help you feel focused, like an award you won or a picture of your favorite colleagues at a team-building event. If you like the comfort of working in bed, use what you can to make working from a desk, couch, or floor more comfortable. Reading pillows and lap desks can be quite versatile.

- Find ways to distinguish where you work from where you sleep. Even if your new desk or “office” lives in your bedroom, find ways to make it feel separate from your bed. Decorate your desk with different colors than your bedding. At night, remove your work devices and move them into another room. Similarly, don’t mix materials you use for sleeping, or as part of your bedtime routine, with your desk environment, like pillows, candles, or the book you read before bed.

- Tune out the office at night. Don’t check work emails in the evening as you’re winding down for bed. Don’t open up your laptop to see if you missed something important. Trust that you can get to it tomorrow, after you’ve had a great night’s sleep.

- Consider replacing your mattress. If your mattress has outlived its lifespan, it may be time for a new one — regardless of whether you’re using it for sleep or work. Check out our guide to knowing when it’s time to replace your mattress, and tips for choosing the right bed. You can keep practicing social distancing by buying a mattress online.

Our Methodology

We surveyed 1,183 Americans using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to 75, with an average of 54 percent of respondents identifying as female, and 46 percent identifying as male.

To keep our data clean, we only compared results among people who had previously worked from home in the last year (n = 1,020). This allowed us to parse out the sleep differences among people who have worked from home in the past, but are now being forced to work from home on a more regular basis due to social distancing guidelines.

While our data does align with similar studies regarding sleep quality, productivity, and mental and emotional wellbeing, it’s important to note that all of the data was self-reported. As a result, it’s subject to the typical biases and limitations inherent with self-reported data, such as selective memory, inaccurate estimation, and over- or under-exaggeration.

Conclusion

Since the Coronavirus outbreak, an unprecedented number of people have suddenly found themselves sheltering-in-place and working from home. With the stress of the pandemic, many are also having trouble getting a healthy amount of sleep each night, and sleeping restfully throughout the night without any disruptions.

The sudden changes brought about by the COVID-19 crisis have led many to create a makeshift office space in their home. Unfortunately, for many, that office has become their bed. Our survey shows that those who work from bed are more likely to have difficulty sleeping, be less productive and more distracted, and to experience pain and/or stiffness while they work.

One solution to working (and coping) better during these times may be to separate our work and sleep environment. By moving our “desks” out of the bedroom, we may sleep more soundly, increase our focus, and be better-equipped to adjust to the new normal of working from home.